Arcadia is a place of rural bliss for some, dispossession for others

Sir Philip Sidney's epic prose evokes an antiquarian paradise. It's based on a lie

There were hilles which garnished their proud heights with stately trees: humble valleys whose base estate semed comforted with refreshing silver rivers: meadows, enameld with al sorts of ey-pleasing floures: thickets, which being lined with most pleasant shade, were witnessed so to by the chereful disposition of many wel-tuned birds.

Who can resist this slice of English pastoral prose written in the 1570s. Even the birds, well tuned and cheerful, pay homage.

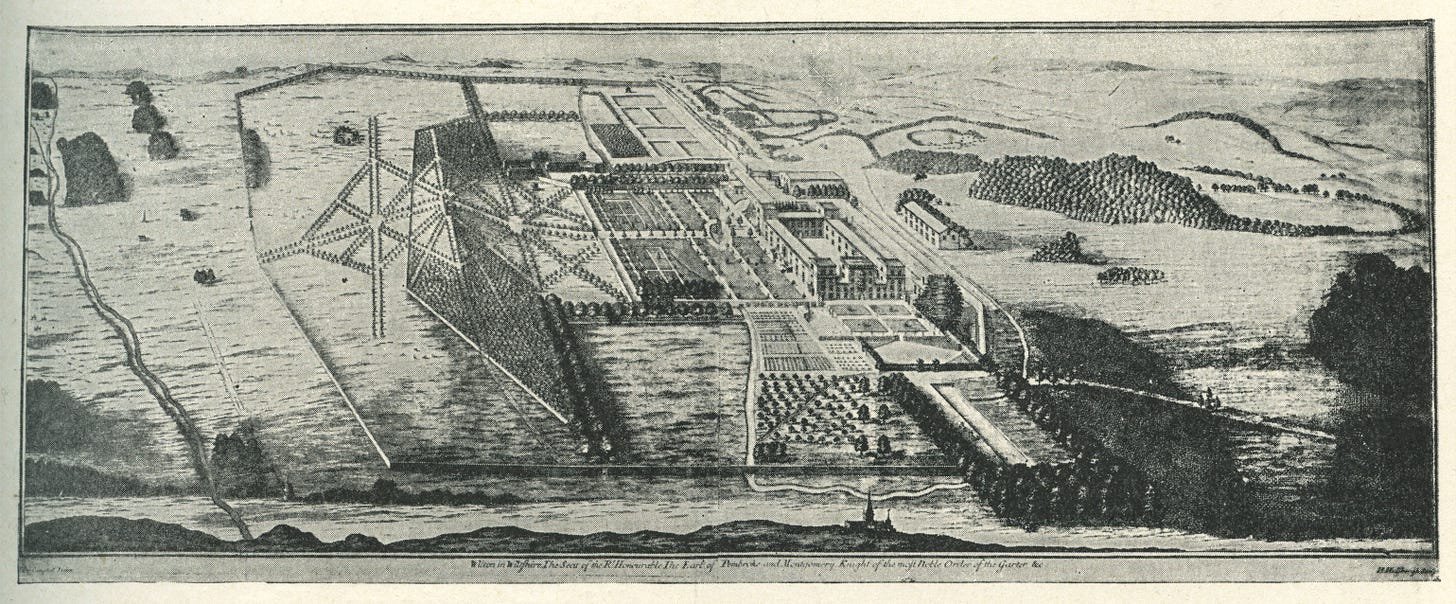

Sir Philip Sidney’s The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia was written for his younger sister Mary (the aforementioned Countess) while he stayed at her country pile, Wilton House in Wiltshire, England.

He actually wrote two versions of this, Old and New, the latter much longer and remaining unfinished by the time of his death at the age of 32 in 1586.

The work was hugely popular in its day with its celebration of the 'sweetnesse of the ayre' and its roaming idealised shepherds.

It perfectly reflects the Renaissance return to the classical idea of Arcadia as a place of rural peace and connection with nature away from the stresses of court life.

It also, as the above quote illustrates, captures the idyllic bliss of the countryside around Wilton experienced by Sidney as he strolled, building the story in his head.

It remains a seminal text today for those studying Arcadian notions of communion with countryside.

It is also a lie.

For there is no beautiful paradise here. At least not for everyone.

The meadows through which Sidney tramped untroubled by anything except the birds did not always belong to Mary. They were harvested, worked and enjoyed by others.

The land was given to Mary’s ancestor, the Earl of Pembroke, by Henry VIII on the dissolution of the monasteries. Wilton Abbey, a Benedictine convent, which had stood there from the 10th Century, was demolished.

Gratified at the King’s largesse the Earl set about building a new house, expanding his land and creating formal gardens.

There was one small problem. On the place he envisaged his deer park there already existed a village, the craft ale sounding, Fugglestone.

For centuries its inhabitants had tilled the land not far from the old Abbey, indeed often supplying the nuns with victuals for small sums.

As I say, only a small problem for the Earl. He simply enclosed the village, evicted the residents, and let the village decay before ‘removing’ it. There would be no Arcadia for these people.

While it was ok for shepherds to wander periodically through paradise, symbolising freedom and simplicity as they did so, permanent reminders of the poor were something else.

The Pembrokes did not want hovels spoiling the vista through their gardens, across the lush park and towards their heavenly destiny.

It wasn’t just peasants who could be off putting. Some landowners had tunnels created for their cows so the livestock could pass from field to field without spoiling the view from the veranda.

The study of the British landscape has a problem with context and people. They tend to go missing. Often physically at first and then historically.

Try finding out anything from academics about Fuggletone while researching either the history of the house, gardens or pastoral prose. At least Wikipedia suggests it was ‘largely extinguished’ by the expansion of the Earl’s park even if it does leave it at that.

It's not just Britain of course. Take the famous 16th Century Italian Renaissance gardens at Villa D’Este at Tivoli near Rome. They’re now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In official histories you will quickly learn how the governor of Tivoli, Cardinal Ippolito d’Este commissioned artist and designer Pirro Ligorio to create a house and gardens on a grander scale than anything the Romans had built.

You will struggle to find much about the gardeners, fontanieres, builders and craftsmen who turned Ligorio’s rough sketches into stunning reality. People are missing from these gardens too.

As are the local residents who in 1568 filed twelve unsuccessful lawsuits to stop them losing their homes under the Cardinals estate expansion plans.

Now and again an alternative narrative pokes its head above the enclosing hedgerow to remind us that landscape history isn’t all parterres, box hedge, Ligorio, Brown and Repton.

Two hundred years after Sidney’s mirage story Lord Harcourt’s efforts to repeat the Earl of Pembroke’s land grab trick at his Nuneham estate in Oxford begat a poetic treatment of a very different kind.

Oliver Goldsmith’s The Deserted Village laments the actions of Harcourt in removing the village of Nuneham Courtenay almost two miles away so he also could create a deer park.

The village street became a path in the park along which (invited) guests could gaze at the lovely valley below.

Ill fares the land, to hastening ill a prey, Where wealth accumulates and men decay: wrote Goldsmith. A warning ignored ever since.

In truth there’s not much other source material for those looking for some kind of socio-economic context to leaven their landscape history.

The work of rural poet and activist John Clare, born a few years after Goldsmith’s poem was published, and Gerrard Winstanley’s anti-enclosure Diggers movement in the 17th Century are two of the exceptions

As with most other parts of historical teaching the ‘Great Man’ theory still seems to hold sway.

In his 1987 book English Cottage Gardens, Edward Hymans, wrote that, ‘between 1760 and 1867 England’s small class of rich men, using as their instrument Acts of Parliament, which they controlled through a tiny and partly bought and paid for electorate, stole seven million acres of common land, the property and livelihood of the common people of England.’

I’m pretty sure the book’s not on the classroom syllabus.

I don’t mean to be facetious here but if we don’t know how the land, gardens and landscape of Britain came to be how they are, how they look, whose hands they are in, who the winners and losers in history have been, we cannot fully understand the country in which we live.

On the days we are allowed in it is certainly worth gazing over the house and gardens at Wilton, or indeed any of Britain’s celebrated houses and landscapes, to appreciate beauty and ornamentation. But perhaps we should also spare a thought for vanished people and their labour and of removal and dispossession.

Then we will have the full story.

Recommended further reading: The Country and the City (Raymond Williams: London 1973)

Vista: The culture and politics of gardens (ed Tim Richardson & Noel Kingsbury: London 2005)